Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

Table of Contents

Honestly, I started writing this article for no real reason, and somewhat

without context, in December 2022—over half a year ago! But, I left it in

_drafts/ until today, when a genuinely compelling scenario came up that gives

real opportunity for explanation. It no longer feels like

trivia-for-the-sake-of-it thanks to a recent client project.

I never thought I’d write an article in defence of DOMContentLoaded, but here

it is…

For many, many years now, performance engineers have been making a concerted

effort to move away from technical metrics such as Load, and toward more

user-facing, UX metrics such as Speed

Index

or Largest Contentful

Paint.

However, as an internal benchmark, there are compelling reasons why some of you

may actually want to keep tracking these ‘outdated’ metrics…

Measure the User Experience

The problem with using diagnostic metrics like Load or DOMContentLoaded to

measure site-speed is that it has no bearing on how a user might actually

experience your site. Sure, if you have Load times of 18 seconds, your site

probably isn’t very fast, but a good Load time doesn’t mean your site is

necessarily very fast, either.

In the comparison above, which do you think provides the better user experience?

I’m willing to bet you’d all say B, right? But, based on DOMContentLoaded,

A is actually over 11s faster!

Load and DOMContentLoaded are internal browser events—your users have no

idea what a Load time even is. I bet half of your colleagues don’t either. As

metrics themselves, they have little to no reflection on the real user

experience, which is exactly why we’ve moved away from them in the first

place—they’re a poor proxy for UX as they’re not emitted when anything useful to

the user happens.

Or are they…?

Technically Meaningful

Not all metrics need to be user-centric. I’m willing to bet you still monitor

TTFB, even though

you know your customers will have no concept of a first byte whatsoever. This is

because some metrics are still useful to developers. TTFB is a good measure of

your server response times and general back-end health, and issues here may have

knock-on effects later down the line (namely with Largest Contentful Paint).

Equally, both DOMContentLoaded and Load aren’t just meaningless browser

events, and once you understand what they actually signify, you can get some

real insights as to your site’s runtime behaviour from each of them. Diagnostic

metrics such as these can highlight bottlenecks, and how they might ultimately

impact the user experience in other ways, even if not directly.

This is particularly true in the case of DOMContentLoaded.

What Does It Actually Mean?

The DOMContentLoaded

event

fires once all of your deferred JavaScript has finished running.

Therefore, anyone leaning heavily on defer—or frameworks that utilise

it—should immediately see the significance of this metric.

If you aren’t (able to) monitoring custom metrics around your application’s

interactivity, hydration state, etc., then DOMContentLoaded immediately

becomes a very useful proxy. Knowing when your main bundles have run is great

insight in lieu of more forensic runtime data, and it’s something I look at with

any client that leans heavily on (frameworks that lean heavily on) defer or

type=module.

More accurately, DOMContentLoaded signifies that all blocking and

defer and type=module code has finished running. We don’t have any

visibility on whether it ran successfully but it has at least finished.

Putting It to Use

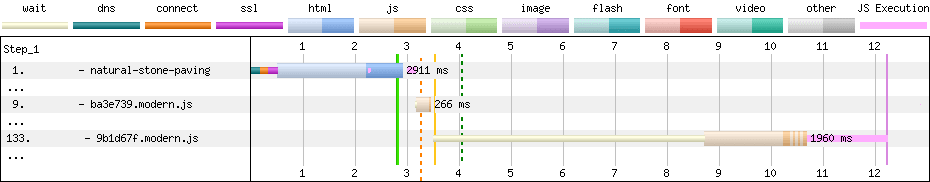

I’m working with a client at the moment who is using Nuxt

and has their client-side JavaScript split into an eyewatering 121 deferred

files:

Above, the vertical pink line at 12.201s signifies the DOMContentLoaded event.

That’s late! This client doesn’t have any RUM or custom monitoring in place (yet), so, other than Core Web Vitals, we don’t have much

visibility on how the site performs in the wild. Based on a 12s

DOMContentLoaded event, I can’t imagine it’s doing so well.

The problem with Core Web Vitals, though, is that its only real JavaScripty

metric, First Input Delay, only deals with user

interaction: what I would like to know is with 121

Based on the lab-based 12sdeferred files, when is

there something to actually interact with?!

above, I would love to know what’s happening for real users. And luckily, while

DOMContentLoaded is now considered a legacy metric, we can still get field

data for it from two pretty decent sources…

Chrome User Experience Report (CrUX)

CrUX Dashboard is one of

very few CrUX resources that surfaces

the DOMContentLoaded event to us. Above, we can see that, currently, only 11%

of Chrome visitors experience a Good DOMContentLoaded—almost 90% of people

are waiting over 1.5s before the app’s key functionality is available, with

almost half waiting over 3.5s!

DOMContentLoaded was 4.7s for 75% of Chrome visitorsin May 2023.

It would also seem that Treo (which is a truly amazing tool)

surfaces DOMContentLoaded data for a given

origin.

Google Analytics

Until, well,

today, Google

Analytics also surfaced DOMContentLoaded information. Only this time, we

aren’t limited to just Chrome visits! That said, we aren’t presented with

particularly granular data, either:

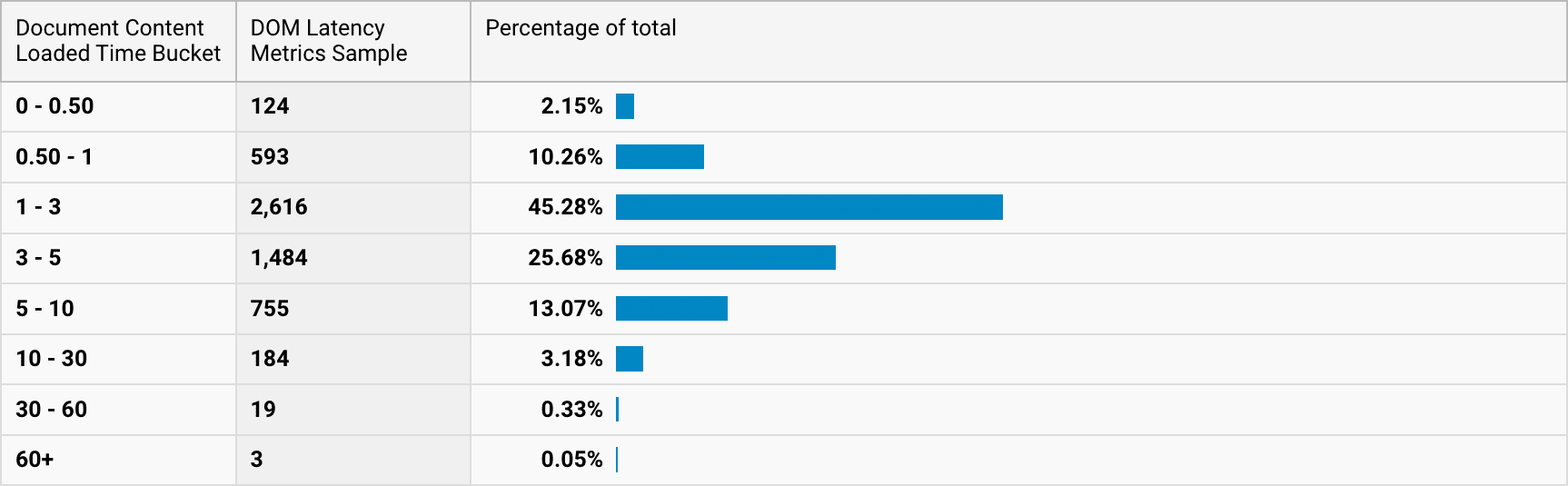

After a bit of adding up (2.15 + 10.26 + 45.28 + 25.68 + 13.07

= 96.44), we see that the 95th percentile of DOMContentLoaded

events for the same time period (May 2023) is somewhere between five and 10

seconds. Not massively helpful, but an insight nonetheless, and at least shows

us that the lab-based 12s is unlikely to be felt by anyone other than extreme

outliers in the field.

Takeaways here are:

- Only about 10% of Chrome visitors have what Google deem to be a Good

DOMContentLoaded. Alldeferred JavaScript has run within 1.5s for only

the vast minority of visitors. - 3.56% of all users waited over 10s for

DOMContentLoaded. This is a 10

second wait for keydeferred JavaScript to run.

Given that the DOMContentLoaded event fires after the last of our

deferred files has run, there’s every possibility that key functionality from

any preceding files has already become available, but that’s not something we

have any visibility over without looking into custom monitoring, which is

exactly the situation we’re in here. Remember, this is still a proxy metric—just

a much more useful one than you may have realised.

Digging Deeper: The Navigation Timing API

If we want to capture this data more deliberately ourselves, we need to lean on

the Navigation Timing

API,

which gives us access to a suite of milestone timings, many of which you may

have heard of before.

The DOMContentLoaded as measured and emitted by the Navigation Timing API is

actually referred to as domContentLoadedEventStart—there is no bare

domContentLoadedEvent in that spec. Instead, we have:

domContentLoadedEventStart: This is the one we’re interested in, and is

equivalent to the concept we’ve been discussing in this article so far. To

get the metric we’ve been referring to asDOMContentLoaded, you need

window.performance.timing.domContentLoadedEventStart.- Because

deferred JS is guaranteed to run after synchronous JS, this event

also marks the point that all synchronous work is complete.

- Because

domContentLoadedEventEnd: The end event captures the time at which all

JS wrapped in aDOMContentLoadedevent listener has finished running:window.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', (event) => { // Do something });- This is separate to

deferred JavaScript and runs after our

DOMContentLoadedevent—if we are running a nontrivial amount of code at

DOMContentLoaded, we’re also interested in this milestone. That’s not in

the scope of this article, though, so we probably won’t come back to that

again.

- This is separate to

Very, very crudely, with no syntactic sugar whatsoever, you can get the page’s

DOMContentLoaded event in milliseconds with the following:

console.log(window.performance.timing.domContentLoadedEventStart - window.performance.timing.navigationStart);

…and the duration (if any) of the DOMContentLoaded event with:

window.performance.timing.domContentLoadedEventEnd - window.performance.timing.domContentLoadedEventStart

And of course, we should be very used to seeing DOMContentLoaded at the bottom

of DevTools’ Network panel:

Even More Insights

While DOMContentLoaded tells us when our deferred code finished

running—which is great!—it doesn’t tell us how long it took to run. We might

have a DOMContentLoaded at 5s, but did the code start running at 4.8s? 2s? Who

knows?!

We do.

In the above waterfall, which is the same one from earlier, only even shorter,

we still have the vertical pink line around 12s, which is DOMContentLoaded,

but we also have a vertical sort-of yellow line around 3.5s (actually, it’s at

3.52s exactly). This is domInteractive. domInteractive is the event

immediately before domContentLoadedEventStart. This is the moment the browser

has finished parsing all synchronous DOM work: your HTML and all blocking

scripts it encountered on the way. Basically, the browser is now at the