Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

Table of Contents

I began writing this article in early July 2023 but began to feel a little

underwhelmed by it and so left it unfinished. However, after

recent and renewed

discussions around the

relevance and usefulness of build steps, I decided to dust it off and get it

finished.

Let’s go!

When serving and storing files on the web, there are a number of different

things we need to take into consideration in order to balance ergonomics,

performance, and effectiveness. In this post, I’m going to break these processes

down into each of:

- 🤝 Concatenating our files on the server: Are we going to send many

smaller files, or are we going to send one monolithic file? The former makes

for a simpler build step, but is it faster? - 🗜️ Compressing them over the network: Which compression algorithm, if

any, will we use? What is the availability, configurability, and efficacy of

each? - 🗳️ Caching them at the other end: How long should we cache files on

a user’s device? And do any of our previous decisions dictate our options?

🤝 Concatenate

Concatenation is probably the trickiest bit to get right because, even though

the three Cs happen in order, decisions we make later will influence

decisions we make back here. We need to think in both directions right now.

Back in the HTTP/1.1 world, we were only able to fetch six resources at a time

from a given origin. Given this limitation, it was advantageous to have fewer

files: if we needed to download 18 files, that’s three separate chunks of work;

if we could somehow bring that number down to six, it’s only one discrete chunk

of work. This gave rise to heavy bundling and concatenation—why download three

CSS files (half of our budget) if we could compress them into one?

Given that 66% of all

websites (and 77% of all

requests) are running

HTTP/2, I will not discuss concatenation strategies for HTTP/1.1 in this

article. If you are still running HTTP/1.1, my only advice is to upgrade to

HTTP/2.

With the introduction of HTTP/2, things changed. Instead of being limited to

only six parallel requests to a given origin, we were given the ability to open

a connection that could be reused infinitely. Suddenly, we could make far more

than six requests at a time, so bundling and concatenation became far less

relevant. An anti pattern, even.

Or did it?

It turns out H/2 acts more like H/1.1 than you might

think…

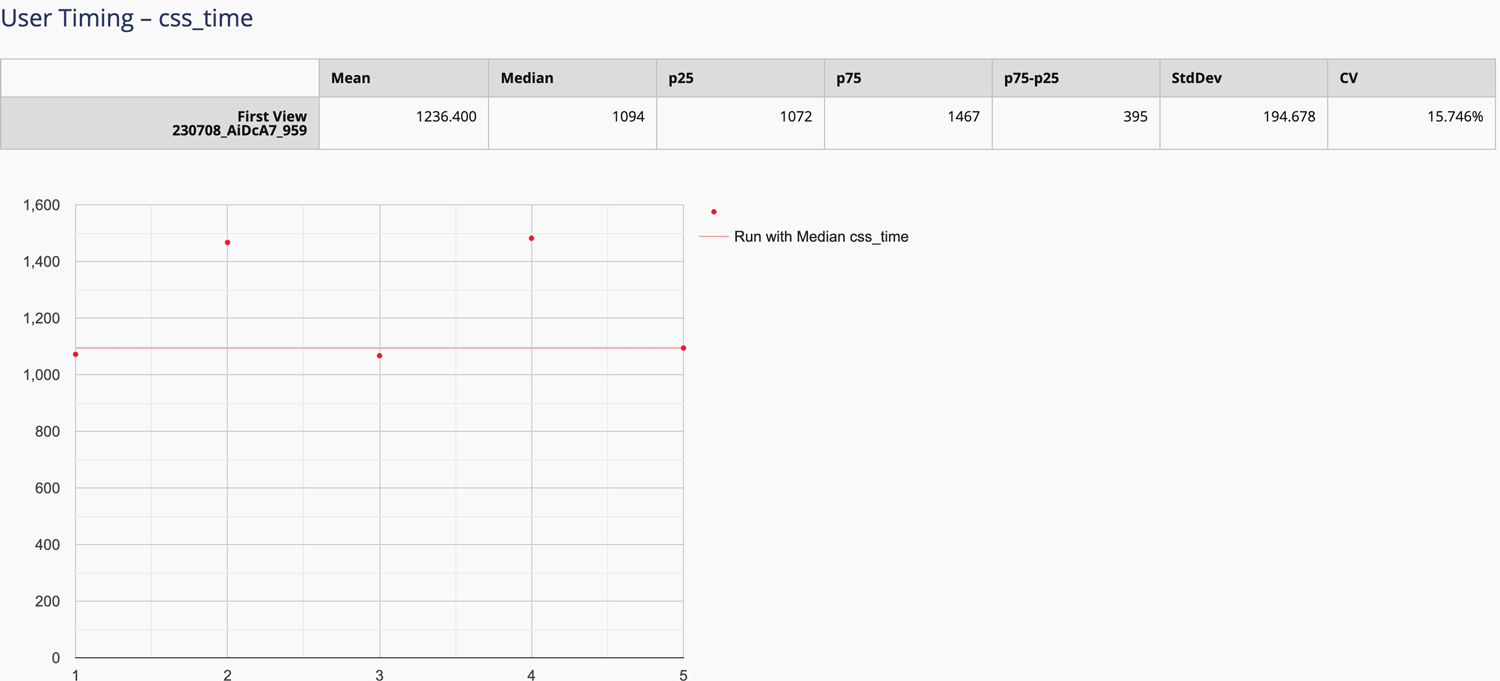

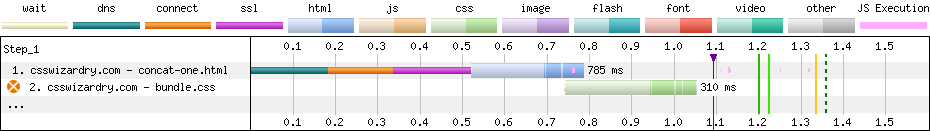

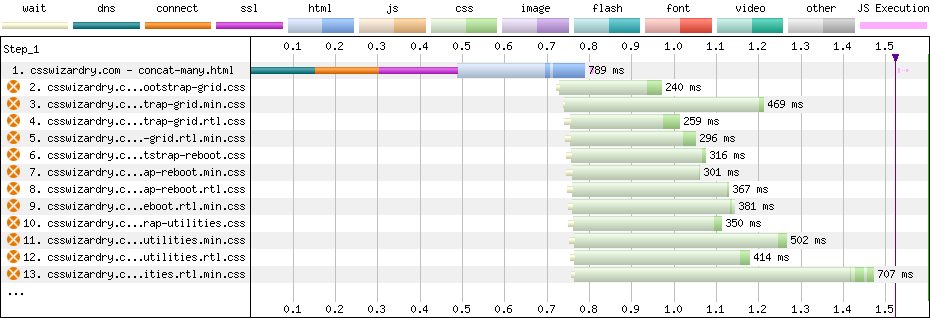

As an experiment, I took the CSS Wizardry homepage and crudely

added Bootstrap. In one test, I concatenated it all into one big file, and the

other had the library split into 12 files. I’m measuring when the last

stylesheet arrives, which is denoted by the vertical purple line. This will

be referred to as css_time.

Read the complete test methodology.

Plotted on the same horizontal axis of 1.6s, the waterfalls speak for

themselves:

With one huge file, we got a 1,094ms css_time and transferred 18.4KB of

CSS.

With many small files, as ‘recommended’ in HTTP/2-world, we got a 1,524ms

css_time and transferred 60KB of CSS. Put another way, the HTTP/2 way

was about 1.4× slower and about 3.3× heavier.

What might explain this phenomenon?

When we talk about downloading files, we—generally speaking—have two things to

consider: latency and

bandwidth. In the

waterfall charts above, we notice we have both light and dark green in the CSS

responses: the light green can be considered latency, while the dark green is

when we’re actually downloading data. As a rule, latency stays

constant while download

time is proportional to filesize. Notice just how much more light green

(especially compared to dark) we see in the many-files version of Bootstrap

compared to the one-big-file.

This is not a new phenomenon—a client of mine suffered the same problem in

July, and the Khan

Academy ran into the same

issue in 2015!

If we take some very simple figures, we can soon model the point with numbers…

Say we have one file that takes 1,000ms to download with 100ms of

latency. Downloading this one file takes:

(1 × 1000ms) + (1 × 100ms) = 1,100ms

Let’s say we chunk that file into 10 files, thus 10 requests each taking

a tenth of a second, now we have:

(10 × 100ms) + (10 × 100ms) = 2,000ms

Because we added ‘nine more instances of latency’, we’ve pushed the overall time

from 1.1s to 2s.

In our specific examples above, the one-big-file pattern incurred 201ms of

latency, whereas the many-files approach accumulated 4,362ms by comparison.

That’s almost 22× more!

It’s worth noting that, for the most part, the increase is parallelised,

so while it amounts to 22× more overall latency, it wasn’t back-to-back.

It gets worse. As compression favours larger files, the overall size of the 10

smaller files will be greater than the original one file. Add to that the

browser’s scheduling mechanisms, we’re

unlikely to dispatch all 10 requests at the same time.

So, it looks like one huge file is the fastest option, right? What more do we

need to know? We should just bundle everything into one, no?

As I said before, we have a few more things to juggle all at once here. We need

to learn a little bit more about the rest of our setup before we can make

a final decision about our concatenation strategy.

🗜️ Compress

The above tests were run with Brotli compression. What happens when we

adjust our compression strategy?

As of

2022,

roughly:

- 28% of compressible responses were Brotli encoded;

- 46% were Gzipped;

- 25% were, worryingly, not compressed at all.

What might each of these approaches mean for us?

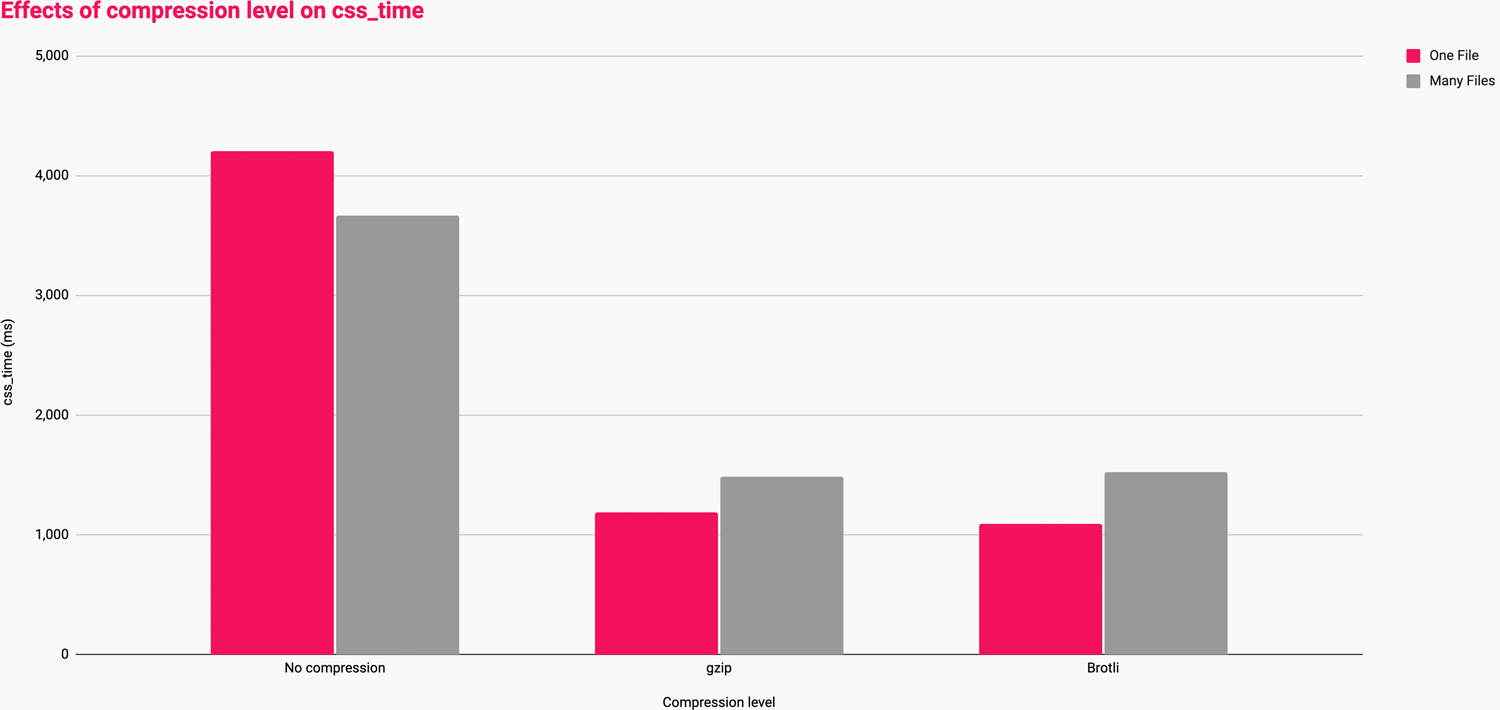

| Compression | Bundling | css_time (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| None | One file | 4,204 |

| Many files | 3,663 | |

| Gzip | One file | 1,190 |

| Many files | 1,485 | |

| Brotli | One file | 1,094 |

| Many files | 1,524 |

faster.

Viewed a little more visually:

size.)

These numbers tell us that:

- at low (or no) compression, many smaller files is faster than one large

one; - at medium compression, one large file is marginally faster than many

smaller

ones; - at higher compression, one large file is markedly faster than many smaller

ones.

Basically, the more aggressive your ability to compress, the better you’ll fare

with larger files. This is because, at present, algorithms like Gzip and Brotli

become more effective the more historical data they have to play with. In other

words, larger files compress more than smaller ones.

This shows us the sheer power and importance of compression, so ensure you have

the best setup possible for your infrastructure. If you’re not currently

compressing your text assets, that is a bug and needs addressing. Don’t optimise

to a sub-optimal scenario.

This looks like another point in favour of serving one-big-file, right?

🗳️ Cache

Caching is something I’ve been obsessed with

lately, but for the

static assets we’re discussing today, we don’t need to know much other than:

cache everything as aggressively as possible.

Each of your bundles requires a unique fingerprint, e.g. main.af8a22.css.

Once you’ve done this, caching is a simple case of storing the file forever,

immutably:

Cache-Control: max-age=2147483648, immutable

max-age=2147483648: This

directive instructs all caches

to store the response for the maximum possible time. We’re all used to

seeingmax-age=31536000, which is one year. This is perfectly reasonable and

practical for almost any static content, but if the file really is immutable,

we might as well shoot for forever. In the 32-bit world, forever is

2,147,483,648 seconds, or 68

years.immutable: This

directive instructs caches

that the file’s content will never change, and therefore to never bother

revalidating the file once itsmax-ageis met. You can only add this

directive to responses that are fingerprinted (e.g.main.af8a22.css)

All static assets—provided they are fingerprinted—can safely carry such an

aggressive Cache-Control header as they’re very easy to cache bust. Which

brings me nicely on to…

The important part of this section is cache busting.

We’ve seen how heavily-concatenated files compress better, thus download

faster, but how does that affect our caching strategy?

While monolithic bundles might be faster overall for first-time visits, they

suffer one huge downfall: even a tiny, one-character change to the bundle would

require that a user redownload the entire file just to access one trivial

change. Imagine having to fetch a several-hundred kilobyte CSS file all over

again for the sake of changing one hex code:

.c-btn {

- background-color: #C0FFEE;

+ background-color: #BADA55;

}

This is the risk with monolithic bundles: discrete updates can carry a lot of

redundancy. This is further exacerbated if you release very frequently: while

caching for 68 years and releasing 10+ times a day is perfectly safe, it’s a lot

of churn, and we don’t want to retransmit the same unchanged bytes over and over

again.

Therefore, the most effective bundling strategy would err on the side of

as few bundles as possible to make the most of compression and scheduling, but

enough bundles to split out high- and low-rate of change parts of your codebase

so as to hit the most optimum caching strategy. It’s a balancing act for sure.

📡 Connection

One thing we haven’t looked at is the impact of network speeds on these

outcomes. Let’s introduce a fourth C—Connection.

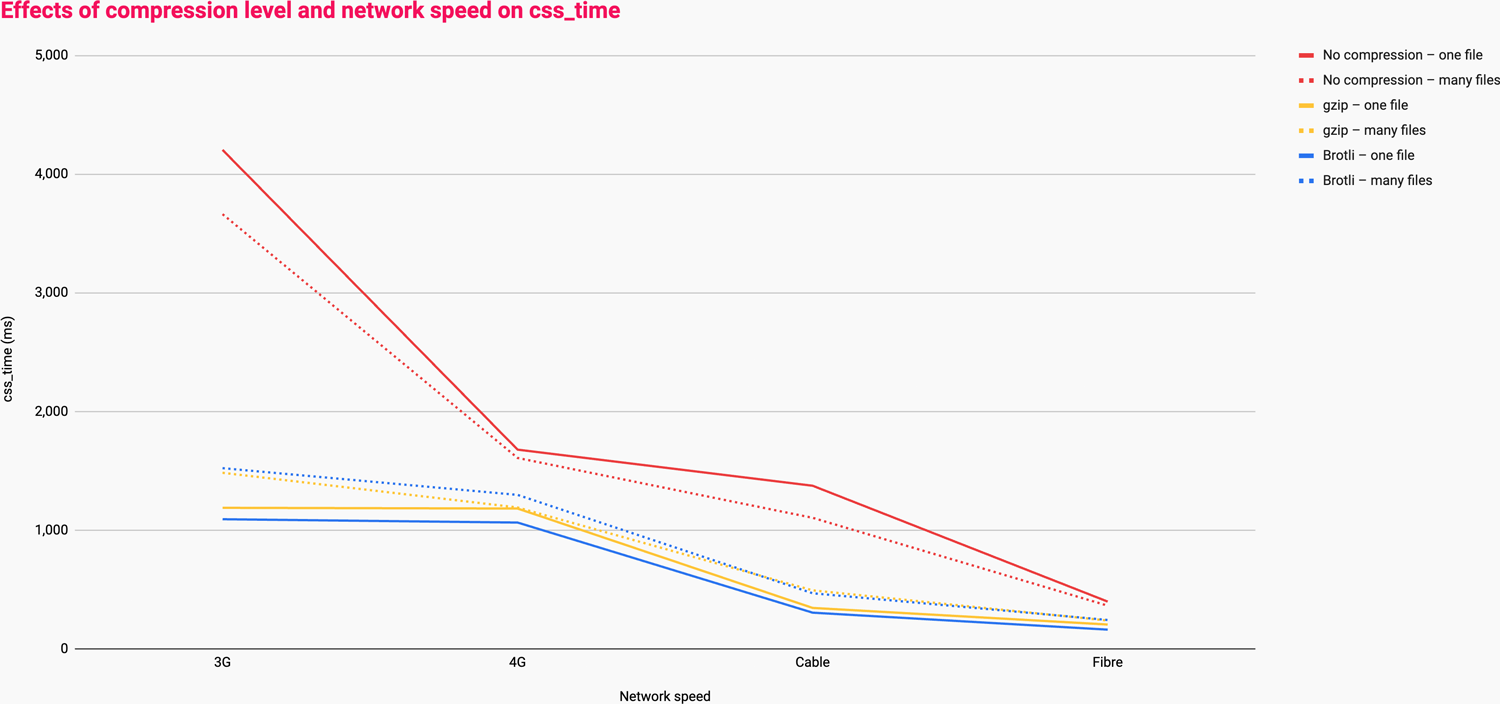

I ran all of the tests over the following connection types:

- 3G: 1.6 Mbps downlink, 768 Kbps uplink, 150ms RTT

- 4G: 9 Mbps downlink, 9 Mbps uplink, 170ms RTT

- Cable: 5 Mbps downlink, 1 Mbps uplink, 28ms RTT

- Fibre: 20 Mbps downlink, 5 Mbps uplink, 4ms RTT

improves. (View full

size.)

This data shows us that:

- the difference between no-compression and any compression is vast, especially

at slower connection speeds;- the helpfulness of compression decreases as connection speed increases;

- many smaller files is faster at all connection speeds if compression is

unavailable; - one big file is faster at all connection speeds as long as it is compressed;

- one big file is only marginally faster than many small files over Gzip, but

faster nonetheless, and; - one big file over Brotli is markedly faster than many small files.

- one big file is only marginally faster than many small files over Gzip, but

Again, no compression is not a viable option and should be considered

a bug—please don’t design your bundling strategy around the absence of

compression.

This is another nod in the direction of preferring fewer, larger files.

📱 Client

There’s a fifth C! The Client.

Everything we’ve looked at so far has concerned itself with network performance.

What about what happens in the browser?

When we run JavaScript, we have three main steps:

- Parse: the browser parses the JavaScript to create an AST.

- Compile: the parsed code is compiled into optimised bytecode.

- Execute: the code is now executed, and does whatever we wanted it to do.

Larger files will inherently have higher parse and compile times, but aren’t

necessarily slower to execute. It’s more about what your JavaScript is doing

rather than the size of the file itself: it’s possible to write a tiny file that

has a far higher runtime cost than a file a hundred times larger.

The issue here is more about shipping an appropriate amount of code full-stop,

and less about how it’s bundled.

As an example, I have a client with a 2.4MB main bundle (unfortunately

that isn’t a typo) which takes less than 10ms to compile on a mid-tier

mobile device.

My Advice

- Ship as little as you can get away with in the first place.

- It’s better to send no code than it is to compress 1MB down to 50KB.

- If you’re running HTTP/1.1, try upgrade to HTTP/2 or 3.

- If you have no compression, get that fixed before you do anything else.

- If you’re using Gzip, try upgrade to Brotli.

- Once you’re on Brotli, it seems that larger files fare better over the

network.- Opt for fewer and larger bundles.

- The bundles you do end up with should, ideally, be based loosely on rate or

likelihood of change.

If you have everything in place, then:

- Bundle infrequently-changing aspects of your app into fewer, larger bundles.

- As you encounter components that appear less globally, or change more

frequently, begin splitting out into smaller files. - Fingerprint all of them and cache them

forever. - Overall, err on the side of fewer bundles.

For example:

vendor.1a3f5b7d.js type=module>

app.8e2c4a6f.js type=module>

home.d6b9f0c7.js type=module>

carousel.5fac239e.js type=module>

vendor.jsis needed by every page and probably updates very

infrequently: we shouldn’t force users to redownload it any time we make

a change to any first-party JS.app.jsis also needed by every page but probably updates more often than

vendor.js: we should probably cache these two separately.home.jsis only needed on the home page: there’s no point bundling it

intoapp.jswhich would be fetched on every page.carousel.jsmight be needed a few pages, but not enough to warrant

bundling it intoapp.js: discrete changes to components shouldn’t require

fetching all ofapp.jsagain.

The Future Is Brighter

The reason we’re erring on the side of fewer, larger bundles is that

currently-available compression algorithms work by compressing a file against

itself. The larger a file is, the more historical data there is to compress

subsequent chunks of the file against, and as compression favours repetition,

the chance of recurring phrases increases the larger the file gets. It’s kind of

self-fulfilling.

Understanding why things work this way is easier to visualise with a simple

model. Below (and unless you want to count them, you’ll just have to believe

me), we have one-thousand a characters:

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

This takes up 1,000 bytes of data. We could represent these one-thousand as as

1000(a), which takes up just seven bytes of data, but can be multiplied back

out to restore the original thousand-character string with no loss of data. This

is lossless compression.

If we were to split this string out into 10 files each containing 100 as, we’d

only be able to store those as:

That’s ten lots of 100(a), which comes in at 60 bytes as opposed to the seven

bytes achieved with 1000(a). While 60 is still much smaller than 1,000, it’s

much less effective than one large file as before.

If we were to go even further, one-thousand files with a lone a character in

each, we’d find that things actually get larger! Look:

harryroberts in ~/Sites/compression on (main)

» ls -lhFG

total 15608

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 1.0K 23 Oct 09:29 1000a.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 40B 23 Oct 09:29 1000a.txt.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 2B 23 Oct 09:29 1a.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 29B 23 Oct 09:29 1a.txt.gz

Attempting to compress a single a character increases the file size from two

bytes to 29. One mega-file compresses from 1,000 bytes down to 40 bytes; the

same data across 1,000 files would cumulatively come in at 29,000 bytes—that’s

725 times larger.

Although an extreme example, in the right (wrong?) circumstances, things can get

worse with many smaller bundles.

Shared Dictionary Compression for HTTP

There was an attempt at compressing files against predefined, external

dictionaries so that even small files would have a much larger dataset available

to be compressed against. Shared Dictionary Compression for HTTP (SDHC) was

pioneered by Google, and it worked by:

…using pre-negotiated dictionaries to ‘warm up’ its internal state prior to

encoding or decoding. These may either be already stored locally, or uploaded

from a source and then cached.

— SDHC

Unfortunately, SDHC was removed in Chrome 59 in

2017. Had it worked out,

we’d have been able to forgo bundling years ago.

Compression Dictionaries

Friends Patrick Meenan and Yoav

Weiss have restarted work on implementing

an SDCH-like external dictionary mechanism, but with far more robust

implementation to avoid the issues encountered with previous attempts.

While work is very much in its infancy, it is incredibly exciting. You can read

the explainer, or

the

Internet-Draft

already. We can expect Origin Trials

as we speak.

The early

outcomes

of this work show great promise, so this is something to look forward to, but

widespread and ubiquitous support a way off yet…

tl;dr

In the current landscape, bundling is still a very effective strategy. Larger

files compress much more effectively and thus download faster at all connection

speeds. Further, queueing, scheduling, and latency work against us in

a many-file setup.

However, one huge bundle would limit our ability to employ an effective caching

strategy, so begin to conservatively split out into bundles that are governed

largely by how often they’re likely to change. Avoid resending unchanged bytes.

Future platform features will pave the way for simplified build steps, but even

the best compression in the world won’t sidestep the way HTTP’s scheduling

mechanisms work.

Bundling is here to stay for a while.

Appendix: Test Methodology

To begin with, I as attempting to proxy the performance of each by taking the

First Contentful Paint milestone. However, in the spirit of measuring what

I impact, not what

I influence,

I decided to lean on the User Timing

API

and drop a performance.mark() after

the last stylesheet:

rel=stylesheet href=...>

const css_time = performance.mark('css_time');

I can then pick this up in WebPageTest using

their Custom Metrics:

[css_time]

return css_time.startTime

Now, I can append ?medianMetric=css_time to the WebPageTest result URL and

automatically view the most

representative

of the test runs. You can also see this data in WebPageTest’s Plot Full

Results view: